Donjon | 12/03/2025

Is Your Smartphone’s Hardware Safe?

The Ledger Donjon dives into smartphone security; testing smartphone chips for vulnerabilities. Here's what they found

Smartphones are commonly lost or stolen, but could that impact your security? The Ledger Donjon targeted a recent SoC to find out exactly how secure today’s smartphones are.

Before You Dive In

- Smartphone security often focuses only on malware and software vulnerabilities.

- Lost or stolen phones are, however, vulnerable to physical attacks, meaning an attacker may target a smartphone’s hardware in addition to its software.

- Applying its hardware security expertise, the Ledger Donjon evaluated a recent smartphone processor chip used in popular smartphones.

- The Ledger Donjon found fault injection vulnerabilities, achieving complete security compromise and arbitrary code execution at the highest privilege level.

Digital self-custody lies at the very heart of the Blockchain revolution: it is both enabled by blockchain technology, and of critical importance to the realisation of its ideals. By fully empowering users however, it brings about stringent requirements for digital security, whose responsibility becomes the users’. The community realised that computers and smartphones, that had long become the alpha and omega of our digital lives, could not possibly provide the security needed for protecting users joining in to the self-custody movement. From malware that users could be tricked into installing on their machines, to fully remote, zero-click exploits commonly used by government-backed entities, there is simply no way to safely store and use one’s private keys on those devices.

This incredibly important realization led to the ideation of the concept of the hardware wallet, a separate, self-reliant device, whose only job is to store and manipulate private keys, making it simple enough to offer only the smallest software attack surface to attackers. Software is only one part of the equation however, and Ledger’s Donjon repeatedly showed that hardware attacks absolutely did have to be part of the threat model of wallets and signers. In particular, we advocated that user’s data security should always be underpinned by a Secure Element, a chip specifically engineered and thoroughly tested (to credit card standards) to resist even advanced hardware attacks if used correctly. This view has now become widely accepted in the ecosystem, and has contributed to significantly raise the overall level of security, even if important nuances in the correct use of Secure Elements do exist in practice.

Invented because of the frailty of computers and smartphones against software attacks then, hardware wallets and signers’ threat model has grown to include hardware attacks. But while a staggering amount of effort has since been continuously invested towards ever improving the software security of computers and smartphones, little work has gone into evaluating their resistance to hardware attacks.

Smartphones’ Physical Security

Smartphones, in particular, are commonly lost or stolen. As users then, entrusting them with our data means trusting that an attacker with physical access to our phone, but no knowledge of our authentication secret (PIN, pattern or passcode), will not be able to access the data inside.

But being in physical possession of a smartphone, instead of having to rely purely on remote attacks (e.g. malware), opens up a lot of potential avenues to attackers. Software-wise, the bottom most parts of the software stack, i.e. boot ROMs and boot loaders, can often only be interacted with via local interfaces (e.g. USB or UART), and run at very high privilege levels, so that even a single vulnerability could provide an attacker with all they need to completely compromise the security of the target smartphone. Vulnerabilities in boot ROMs are also not patchable by software updates (because the program is hard coded into the very silicon of the smartphone’s SoC [1]), so that users stay vulnerable even if the vulnerability is disclosed.

Boot ROMs and boot loaders however only expose a quite restricted software attack surface, with much, much less code than what makes up the later parts of the stack (OS and applications). In spite of that, devastating vulnerabilities were found in the past, for instance the checkm8 vulnerability in iPhones, or the handful of vulnerabilities targeting Mediatek SoCs. These vulnerabilities have been patched in newer generations of SoCs, and no equivalent vulnerabilities have been published since.

We therefore wondered if hardware attacks could be used instead to target these early boot stages.

Mediatek Dimensity 7300 / MT6878

We wanted to look at a recent SoC, built on an advanced semiconductor process node, and used in popular smartphones. Based on these criteria, we settled on the Mediatek Dimensity 7300 (which seems to be the commercial name, with a corresponding technical name of MT6878), which is used in many android phones. It is built on a 4nm process node, by TSMC.

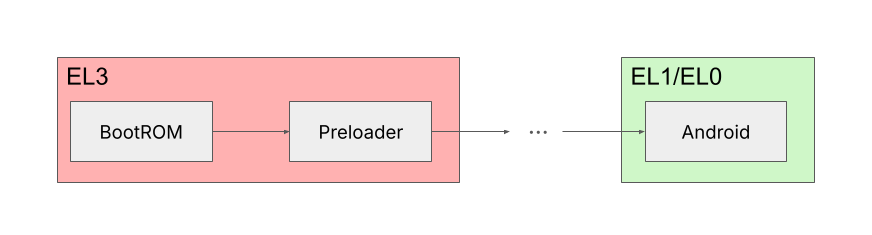

On all of these phones then, before Android has a chance to run, the SoC itself is bootstrapped, and the boot ROM is the very first piece of code that gets executed – and it executes at the highest possible privilege level (EL3), while Android is contained to the lowest privilege levels (EL1 and EL0). The boot ROM’s main role is normally to load the next boot stage (a boot loader, called the preloader by Mediatek) from the smartphone’s main flash memory, into RAM, verify its signature to ensure its integrity and authenticity, and hand execution over to it. However if no valid preloader is found in flash memory [2], then the boot ROM exposes a simple command handler over local interfaces (UART or USB), which is meant to help diagnose, debug and fix the boot process.

Setting Up For EMFI

Among the available commands, two seemed particularly interesting to us as attackers: they allow us to issue READs and WRITEs to the memory subsystem, from the processor. However we of course cannot read or write to any address, and there is in fact a very strict filtering applied to the requests based on a severely limiting whitelist. We therefore decided to try and use the same tools and techniques that we commonly use on microcontrollers, and inject faults into the processor during the execution of these commands, so as to bypass this security check. If successful, this would then allow us to read or write from anywhere in the address space, which is a very strong primitive and often a critical stepping stone towards gaining arbitrary code execution.

The Ledger Donjon has released comprehensive open-source tooling over the years, in order to demystify and facilitate independent research on hardware attacks. For fault injection specifically, one very powerful and accessible technique is Electro-Magnetic Fault Injection (EMFI). Its principle of operation is very simple: a strong electrical current is pulsed through a coil of wire, thereby generating a strong, pulsed electromagnetic field in the immediate vicinity of the coil. When subjected to this field, the operation of processors can end up being disturbed to the point where they no longer correctly execute the software that runs on them, but instead skip instructions, corrupt registers, etc. This can in turn have devastating consequences security-wise, if an attacker is able to precisely target one or a few instructions, for instance skipping a call to a function implementing security checks.

EMFI is very useful because it can be performed without having to modify the PCB onto which the target chip is soldered [3]. For smartphones, this means we can simply open them up and unscrew the main PCB, that usually includes at least the SoC and the flash storage component, and instrument it directly using the open-source Scaffold board. This way, both the battery and USB power sources can be replaced by standard lab power supplies and switched on and off programmatically, and fault injection can be performed based on UART communication with very precise triggering. The only thing we need to do is find where the UART RX and TX lines run on the PCB, but this is easy enough to do by probing the PCB while boot looping the device, and looking for characteristic activity.

The fault injection itself is then performed using the open-source SiliconToaster, with a pulse whose timing and duration are tightly controlled by the Scaffold. The timing of the fault is often the most critical, and hard to find, parameter, as it determines what operations (say, one to a few instructions) are going to be disturbed. To separate the different concerns then, we decided to first find an appropriate pulse width, as well as an appropriate position of the SiliconToaster above the SoC, where we could reliably observe disturbances to the normal execution of the boot ROM and preloader. This is not too hard to do, as both the boot ROM and the preloader emit a fair amount of logs over UART at boot, so that we can observe any variations in the emitted logs, and attribute this change to the effects of the EM pulse.

Gaining Arbitrary Code Execution

With the ability to disturb the execution on the SoC, we then turned our focus to the READ command. Indeed while the preloader binary can be dumped from flash, or found in OTA updates, we did not have access to the boot ROM binary, which we knew would be very useful to have in order to try and find attack paths. We hypothesized that the boot ROM might be mapped at address 0x0, and tried to issue a READ command to this address. Of course without fault injection, the boot ROM’s security checks on the address kick in and we only get an error status, but no data. Our hope was to fault precisely those security checks, and read out the boot ROM binary chunk by chunk. Instead, we observed very peculiar perturbations, where a huge amount of seemingly nonsensical, but deterministic data was sometimes emitted by the boot ROM over UART – way more data than we asked for in the READ command.

Click for more technical details

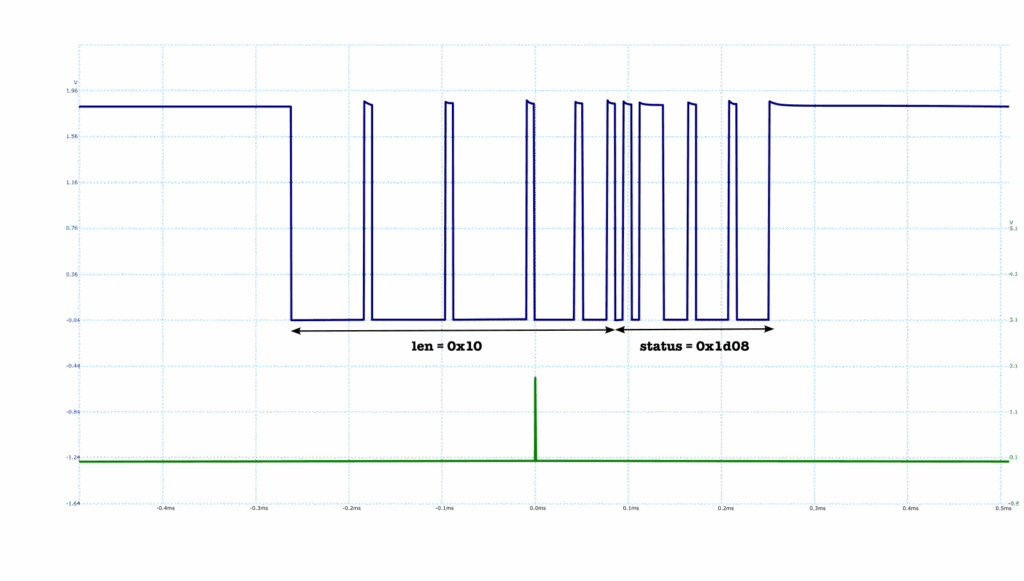

In a bit more detail, the READ command expects us to send it a 4-byte address at which we want to read, and echoes it back to us. It then expects us to send it a 4-byte length, which is the number of words (or half-words – there are actually two variants of the READ command) that we want to read. It, again, echoes this back to us, and then sends a 2-byte status, which is 0x0000 when the read is authorized, and 0x1d08 when it is not. The latter is what we get when we try to read from address 0x0, where we hypothesized the boot ROM might be mapped. Everything in this protocol is always encoded in big-endian. And this is what the echoed length and status look like on the oscilloscope when probing the UART TX line coming from the SoC:

The green trace is the EMFI pulse control from the Scaffold, which controls the release of the EM pulse generated by the SiliconToaster. Here this pulse did not suffice to inject a fault into the processing of the READ command, and we got the regular error status 0x1d08.

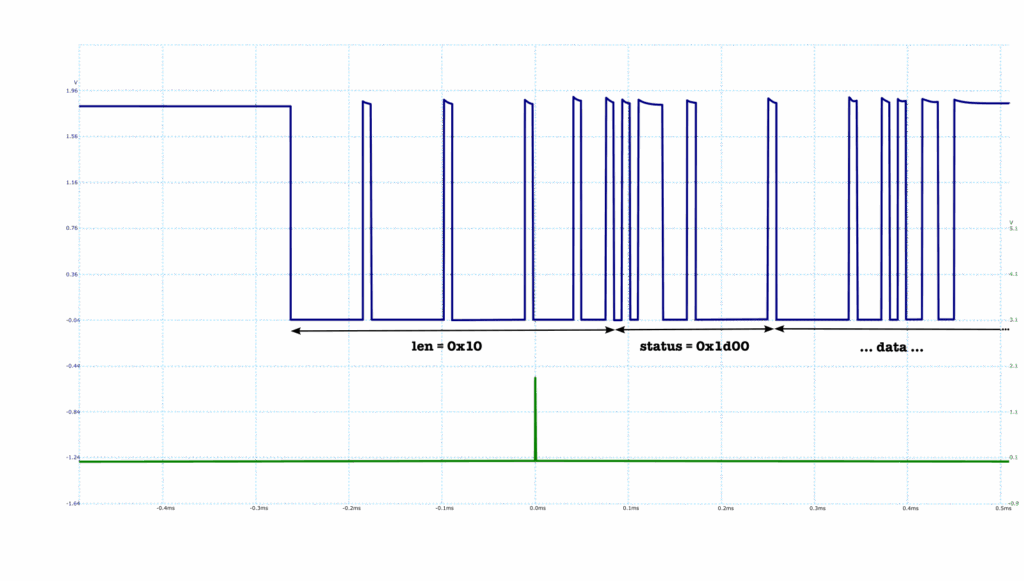

The unexpected fault we observed, however, looked like this on the oscilloscope:

We obtained what looked like a different error status, 0x1d00, followed by a lot (much more than the 0x10 words we had asked for) of deterministic data. At first we tried to interpret this data in big-endian, as used everywhere in the command handler, and could not make sense of it. But it turned out that the 0x1d and 0x00 are not part of a status, but rather part of the data, and that everything had to be interpreted in little-endian instead!

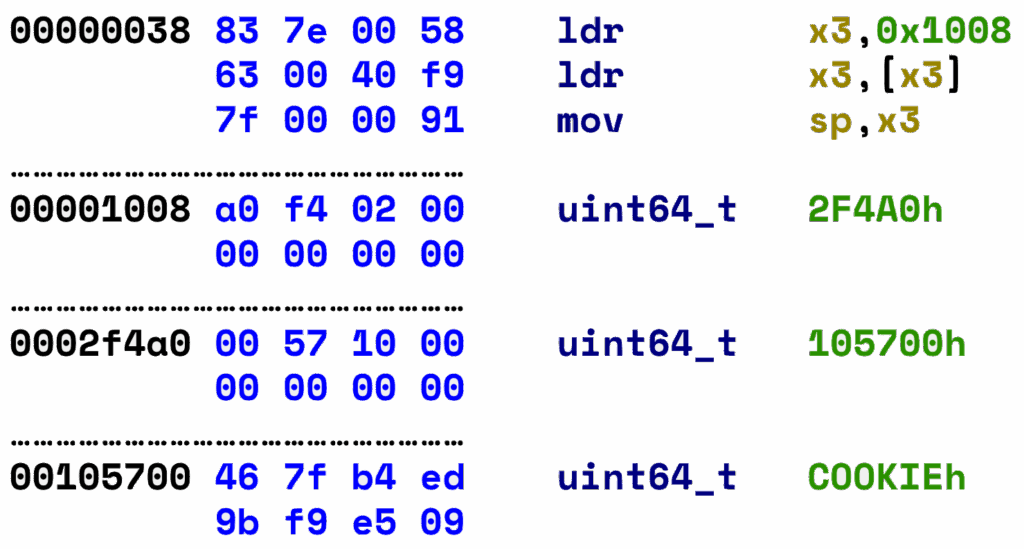

We dug into this data, and to our uttermost surprise, we realised that this was actually a full, linear dump of the whole boot ROM address space, starting from address 0x0. The dump therefore contained all the boot ROM binary (which was indeed mapped at 0x0, as we had hypothesized), but also the dump of the RAM used by the boot ROM during its execution, so that we had essentially a snapshot of the full system state during execution of the READ command. This is not the fault we were aiming for, but it gave us all we needed and more.

Equipped with all this new information, we started to form a more precise idea for an attack path. Under normal circumstances, the WRITE command does not let us write to the boot ROM’s RAM, where its stack is located. But if, just like we intended to do for the READ command, we managed to bypass the command’s security checks by injecting EM pulses at just the right moment, then we could write arbitrary data anywhere into the boot ROM’s RAM. This gave us the idea of trying to overwrite the return address of the WRITE command, stored on the stack at a deterministic address that we now knew, to obtain a powerful primitive called Return Oriented Programming (ROP) very often used in software exploitation.

Click for more technical details

With the boot ROM dumped, it is very easy to understand the stack layout, which is fully deterministic. We can find the snippet of machine code that first sets up the stack pointer, shortly after reset, and then statically follow the function calls up to the WRITE command handler to find the exact address at which the latter’s return address is stored.

A cookie, randomly generated at every boot, is used to mitigate standard buffer overflow vulnerabilities, but it does not matter in our case as we can write to wherever we want directly – we are not limited to a linear overflow from a buffer allocated lower on the stack.

When the WRITE command handler function returns to its caller, then, it retrieves the now-overwritten return address from the stack, and jumps to it, kicking off the ROP chain.

After a few days, we managed to do just that: precisely fault the WRITE command security checks, so as to overwrite the return address on the stack and redirect control flow to wherever we want. From this primitive, we were then able to deactivate the Memory Management Unit (MMU) to make the stack executable [4], so that we could simply write and compile code and have it run on the SoC. This is extremely powerful, and especially so because the boot ROM runs at the most privileged execution level on the processor (namely EL3, as standardized by ARM), so that we have full and absolute control over the smartphone, with no security barrier left standing. What’s more the attack’s success rate is in the 0.1% to 1% range, which, given that we can try to inject a fault every 1 second or so (we repeatedly boot up the device, try to inject the fault, and if the fault does not succeed, we simply power up the SoC and repeat the process), means that we achieving code execution is only a matter of a few minutes.

Conclusion

This experiment confirmed what we very strongly suspected, namely that even complex chips built on the most advanced process nodes can be vulnerable to fault injection, using the very same tools that have been developed and open-sourced by the Ledger Donjon.

Smartphones’ threat model, just like any piece of technology that can be lost or stolen, cannot reasonably exclude hardware attacks. But the SoCs they use are no more exempt from the effects of fault injection than microcontrollers are, and security should really ultimately rely on Secure Elements, especially for self-custody.

Timeline & Disclosure

We started working on this in February 2025, and got arbitrary code execution in the boot ROM in the first days of May 2025. We then disclosed the issue to Mediatek’s security team, which proved very responsive and constructive. They have since informed all the affected OEM vendors.

Here is Mediatek’s assessment of this vulnerability:

“Hardware EMFI (Electromagnetic Fault Injection) attacks are out of scope for the MT6878 chipset. Like many standard microcontroller circuits, the MT6878 chipset is designed for use in consumer products, not for applications such as finance or HSMs (Hardware Security Modules). Therefore, it is not specifically hardened against EMFI hardware physical attacks. For products with higher hardware security requirements, such as hardware crypto wallets, we believe that they should be designed with appropriate countermeasures against EMFI attacks.”

By Charles Christen and Léo Benito,

With help from Baptistin Boilot

Security Engineers

- System-on-Chip, really the smartphone’s processor chip ↩︎

- Which an attacker can easily enforce by shorting the clock line of the flash interface, for instance ↩︎

- Which is not the case for other commonly used fault injection methods, like voltage glitching ↩︎

- The stack is configured to be only readable and writable, but not executable, during execution of the boot ROM ↩︎